Presidents’ Day has taken on a new meaning for me in 2017. The chaos and uproar of the recent presidential election is slowly subsiding, but the aftermath has left me wondering about the state of our union—and what the great presidents of the past would think of the turmoil of today. In past elections, Americans seemed to be able to come together rather quickly for the good of our nation. Not so this time. And that is perhaps the most telling aspect of just how divided we are as a nation.

This division is not new to our nation, and we can work through it. But to do so, we must truly understand what democracy is—and the responsibilities that come with our inalienable rights to freedom. Because freedom isn’t free. It takes a lot of work, and it takes everybody working together. Just ask George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. We are beneficiaries of their effort—as well as all of those who helped them. We can learn a lot from our national leaders of the past—and in doing so we can protect our future.

Our Founding Fathers

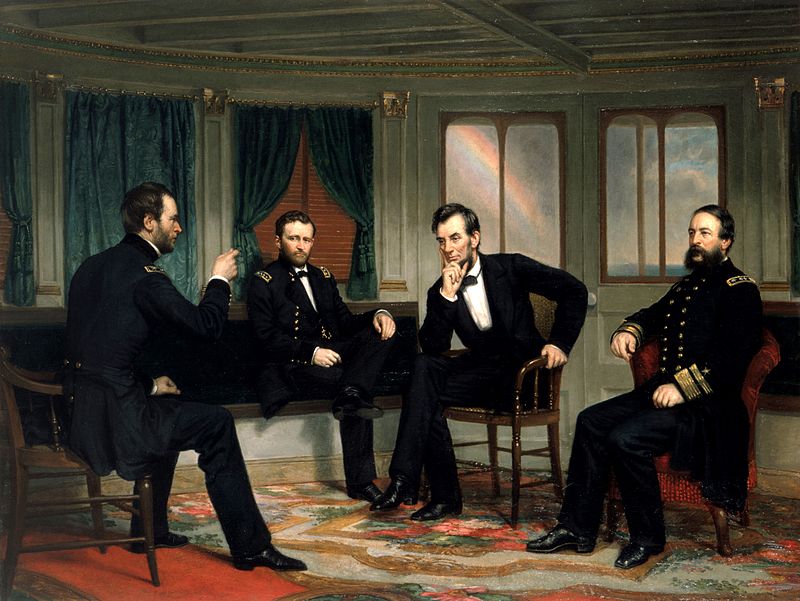

Washington at Constitutional Convention of 1787, signing of U.S. Constitution, by Junius Brutus Stearns.

While Presidents’ Day is specifically set aside to honor our presidents, it is difficult to fully appreciate what we have without first discussing what it took to build our government. President Ezra Taft Benson said,

At the close of the Revolution, the thirteen states found themselves independent but then faced grave internal economic and political problems. The Articles of Confederation had been adopted but proved to be ineffectual. Under this instrument, the nation was without a president, a head. There was a congress, but it was a body destitute of any power. There was no supreme court. The states were merely a confederation. …

Because of this crisis, fifty-five of the seventy-four appointed delegates reported to the convention, representing every state except Rhode Island, for the purpose of forming “a more perfect union.”

It wasn’t an easy task. But in the end, the framers of our Constitution created a document that still stands today. President Benson continued,

What those framers did can be better appreciated when it is considered that when the instrument went into operation, it covered only thirteen states with fewer than four million people. …The wisdom of these delegates is shown in the genius of the document itself. The founders had a strong distrust for centralized power in a federal government. So they created a government with checks and balances. This was to prevent any branch of the government from becoming too powerful.

Congress could pass laws, but the president could check this with a veto. Congress, however, could override the veto, and by its means of initiative in taxation, could further restrain the executive department. The Supreme Court could nullify laws passed by the Congress and signed by the president. But Congress could limit the Court’s appellate jurisdiction. The president could appoint judges for their lifetime with the consent of the Senate.

Each branch of the government was also made subject to different political pressures. The president was to be chosen by electors, Senators by state legislatures, representatives by the people, and the Supreme Court by the president, with the consent of the Senate.

All this was deliberately designed to make it difficult for a majority of the people to control the government and to place restraints on the government itself. The founders created a republic which Jefferson described as “action by the citizens in person in affairs within their reach and competence, and in all others by representativ …” (Paul L. Ford, ed., Works of Thomas Jefferson, New York: J. P. Putnam Sons, 1905, 11:523).

They created a form of government that required citizens to be part of the process.

Washington’s Democracy

We must truly understand democracy and what it means if we are to understand what our role is in it. Jean Bethke Elshtain, at the time a professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School, said,

Democracy is not and has never been primarily a means whereby popular will is tabulated and enacted but, rather, a political world within which citizens deliberate, negotiate, compromise, engage, and hold themselves and those they choose to represent them accountable for actions taken. Have we lost this deliberative and dialogical dimension to democracy? For democracy’s enduring promise is that democratic citizens can come to know a good in common that they cannot know alone (Democracy at Century’s End, BYU Speeches, October 29, 1996).

The responsibility of each citizen to join the discussion also necessitates each person to study the issues for himself or herself as well as to see things from another point of view. Professor Elshtain continued,

Alexis de Tocqueville, in his classic work Democracy in America, argued that one reason the American democracy he surveyed was so sturdy was that citizens took an active part in public affairs. This is important because participating in public affairs means one must move from exclusive and narrowly private interests and occasionally take a look at matters that concern others. In Tocqueville’s words,

As soon as common affairs are treated in common, each man notices that he is not as independent of his fellows as he used to suppose and that to get their help he must often offer his aid to them (Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. J. P. Mayer, trans. George Lawrence, New York: Harper Perennial, 1988, p. 510).

In this way civic engagement helped to underscore what Tocqueville called “self-interest properly understood,” an interest that was never narrowly focused on the self (p. 526). If Tocqueville were among us today, he would no doubt share the concern of social scientists who have researched the sharp decline in participation. They argue that the evidence points to nothing less than a crisis in “social capital formation,” the forging of bonds of social and political trust and competence. The debilitating effects of rising mistrust, privatization, and anomie are many.

Democracy, then, is less about getting what we want and more about creating a solid foundation for our communities—and, in turn, our families.

Lincoln’s Fight for Unity

While Washington is associated with the birth of our government, Lincoln’s role was to preserve our unity. His famous quote, “A house divided cannot stand,” still applies today. While our Founding Fathers created the foundations of our government, they left one glaring issue to be resolved: slavery. The issue of slavery was, in reality, a continuation of the battle for human rights that began with the Declaration of Independence. President Benson said,

The Declaration of Independence was to set forth the moral justification of a rebellion against a long-recognized political tradition—the divine right of kings. At issue was the fundamental question of whether men’s rights were God-given or whether these rights were to be dispensed by governments to their subjects. This document proclaimed that all men have certain inalienable rights. In other words, these rights came from God. Therefore, the colonists were not rebels against political authority, but a free people only exercising their rights before an offending, usurping power.

America could not be a unified nation when a large portion of the population was still denied their inalienable, God-given rights. The Southern States didn’t see things the same way, and decided that they no longer wanted to be part of this Union. So they tried to secede and form their own government. The result was the American Civil War, which pitted brother against brother, father against son and divided a nation.

The North won, and re-unified the nation. But as the decades have marched on and more than a century has passed, Americans have been trying to redefine what freedom truly means. In doing so, the foundation ideals upon which our nation was founded have come into question.

The Quest for True Freedom

True freedom is only found within the bounds of self-restraint. Our Founding Fathers understood that the concept of a citizen-involved government presupposed that said citizens know how to behave themselves properly. British statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke said,

Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains on their own appetites. . . . Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere; and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters (The Works of the Right Honorable Edmund Burke, vol. 4, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1889, pp. 51-52).

The guiding principles for the people must come from within—not from external forces. Elder M. Russell Ballard taught,

Believe it or not, at one time the very notion of government had less to do with politics than with virtue. According to James Madison, often referred to as the father of the Constitution: “We have staked the whole future of American civilization not upon the power of the government—far from it. We have staked the future of all of our political institutions upon the capacity of each and all of us to govern ourselves according to the Ten Commandments of God” (Russ Walton, Biblical Principles of Importance to Godly Christians, New Hampshire: Plymouth Foundation, 1984, p. 361).

George Washington agreed with his colleague James Madison. Said Washington: “Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle” (James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the President, 1789–1897, U.S. Congress, 1899, vol. 1, p. 220).

This internal compass comes from belief in a higher power, in something greater than yourself. Elder Ballard said,

Madison, Washington, and Lincoln all understood that democracy cannot possibly flourish in a moral vacuum and that organized religion plays an important role in preserving and maintaining public morality.

Thus, the framers of the Constitution built in special protections for freedom of religion.

The Threat to Our Liberties

Our Founding Fathers understood the importance of religion in public life. But times have changed. Elder Ballard said,

Our government is succumbing to pressure to distance itself from God and religion. Consequently, the government is discovering that it is incapable of contending with people who are increasingly “unbridled by morality and religion.” A simple constitutional prohibition of state-sponsored church has evolved into court-ordered bans against representations of the Ten Commandments on government buildings, Christmas manger scenes on public property, and prayer at public meetings. Instead of seeking the “national morality” based on “religious principle” that Washington spoke of, many are actively seeking a blind standard of legislative amorality, with a total exclusion of the mention of God in the public square.

Such a standard of religious exclusion is absolutely and unequivocally counter to the intention of those who designed our government. Do you think that mere chance placed the freedom to worship according to individual conscience among the first freedoms specified in the Bill of Rights—freedoms that are destined to flourish together or perish separately? The Founding Fathers understood this country’s spiritual heritage. They frequently declared that God’s hand was upon this nation, and that He was working through them to create what Chesterton once called “a nation with the soul of a church” (Richard John Neuhaus, A New Order for the Ages, speech delivered at the Philadelphia Conference on Religious Freedom, 30 May 1991). While they were influenced by history and their accumulated knowledge, the single most influential reference source for their work on the Constitution was the Holy Bible.

But while Americans in the early days were mostly God-fearing people, the same cannot be said of us today. Elder Dallin H. Oaks said,

I am convinced that a worldwide tide is currently running against both religious freedom and its parallel freedoms of speech and assembly.

I believe religious freedom is declining because faith in God and the pursuit of God-centered religion is declining worldwide. If one does not value religion, one usually does not put a high value on religious freedom. It is looked at as just another human right, competing with other human rights when it seems to collide with them. I believe the freedoms of speech and assembly are also weakening because many influential persons see them as colliding with competing values now deemed more important. Some extremists have even opposed free speech as an obstacle to achieving their policy goals.

Another threat to our liberties comes from our lack of civil discourse one with another. As Professor Elshtain said,

[Our] public-spiritedness is in jeopardy. Our social fabric is frayed. Our trust in our neighbors is low. We don’t join as much. We give less money, as an overall percentage of our gross national product, to charity. Where once rough-and-tumble yet civil politics pertained, now we see “in your face” and “you just don’t get it.”

The result is that instead of internal restraints controlling the actions of American citizens, the government is stepping in and exerting external controls. And when that happens, we lose some of the freedom that we once enjoyed.

Kennedy’s Call to Action

This brings us to John F. Kennedy’s call to action. JFK is famous for saying, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” The first thing that we can do is to become actively engaged in community affairs.

Why is this important? Lawrence C. Walters, at the time a professor in the BYU Romney Institute of Public Management, said,

… Thomas Jefferson penned: “A nation, as a society, forms a moral person, and every member of it is personally responsible for his society.”

This is a weighty thought—that we are each personally responsible for our society…. We are each accountable for the quality of governance in our communities and nations. But we are not asked to bear this responsibility alone. Our lives are interconnected with others’. Our capacities are enhanced and our possibilities expanded through cooperation and collaboration. Because of our shared responsibility and because we are so much more effective together than we are individually, as active citizens we must actively engage with others (Citizenship, BYU Speeches, April 1, 2014).

Engaging with others requires much of oneself—not just in terms of time but also in terms of interpersonal relations. Professor Walters continued,

We must cultivate the ability to participate in collective reasoning…. Such reasoning involves joining with others to identify issues and concerns, giving and receiving information, and taking counsel together. In this process citizens actually listen to others with a desire to understand their views. They ask questions they don’t know the answers to. They respect others, and they respect the decision process.

Inevitably, deliberative processes such as the one I have described identify conflicting points of view. When that happens, active citizens don’t give up but look for common ground and seek to build on a foundation of common understanding. We build relationships, coalitions, and networks as we patiently strive to reach joint decisions.

In a nation as richly diverse as ours, this is no easy task. Even in small communities, people have opposing points of views and differing personalities. It takes real effort, sometimes, to get along. Professor Walters agreed,

There is no question that serious deliberation with people we don’t agree with can be slow and frustrating—especially if we want the Lord’s help, because then we have to get rid of all those unkind thoughts so that the Spirit can be unrestrained. My experience suggests that we make much more progress when we put aside the idea that people who don’t agree with us are ignorant of the facts, stupid, or evil and focus instead on what we have in common. … Active citizens must strive to synthesize and reconcile conflicting views, values, and priorities. This is not easy to do…. It requires that we place the well-being of all on an equal footing and that we always balance the common good against individual claims.

But that is exactly what Kennedy was asking each one of us—what are we willing to do for our country?

The People and the President

One inescapable fact of democracy in America is that we don’t always agree—even (and perhaps especially) on whom to elect as president. This has ever been so. And the elections have become more and more divisive in recent years. The 2016 election is a prime example. But political pundit and journalist Garry Gadfly reminded us,

[In an election year] we get the presidents we deserve. A great people is what you need for a great president. Washington was the greatest president, because the people were at their most enlightened and alert. [America] right now is escapist. It wants to be soothed, and told it doesn’t have to pay or sacrifice or learn (Things That Matter, Vis a Vis, July 1988, p. 70).

Americans can’t escape the fact that they are responsible for electing our president. We can help make him (or her) great by doing our part and helping to build up our nation, one community at a time, or not. We can seek to be soothed or we can pay, sacrifice and learn how to do better. Half of the people voted for President Trump, and half voted for Hillary Clinton in this election. The split has been about the same for the past few elections—which means that half of the country are happy and half are mad each time the election results are in.

This makes our response as a nation even more important. Will we decide to work together for the common good, or continue fighting each other? Will we stand behind the president, even if we belong to the half who didn’t vote for him? When we do, we honor the presidents of the past and what they worked so hard to build. When we don’t, we put the future of our nation in jeopardy. Because, as Lincoln taught us, a house divided cannot stand.

We would be wise to follow the counsel of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who said following the November election,

We congratulate President-elect Donald Trump on his election as president of the United States.

We invite Americans everywhere, whatever their political persuasion, to join us in praying for the president-elect, for his new administration and for elected leaders across the nation and the world. Praying for those in public office is a long tradition among Latter-day Saints. The men and women who lead our nations and communities need our prayers as they govern in these difficult and turbulent times.

We also commend Secretary Hillary Clinton and all those who engaged in the election process at a national or local level. Their participation in our democratic process, by its nature, demands much of those who offer themselves for public service. May our local and national leaders reflect the best in wisdom and judgment as they fulfill the great trust afforded to them by the American people.